|

Mike

Estelmann

Perhaps

no other military decoration is as significant as the Iron

Cross. At a minimum, this statement is true for the

foundation year series of 1813 and, at a respectful

distance, the 1870 series. The historical dimension, the

engaging symmetrical aesthetic, and the appealing

juxtaposition of two metals which could not be more

different from one another, only begin to explain why

contemporary examples of this patriotic decoration are in

such high demand. As this demand is now so high, and there

are an insufficient number of originals, there has followed

what must: modern copies. These copies may be revealed

through the use of relevant literature, photo documentation,

and comparative analysis with known originals. To begin

with, of course, we have the words of the Old Master of

Prussian Militaria-writing. Louis Schneider, the Privy Court

Councilor and Reader of his Majesty the King, notes in his

1872 work, The Book of the Iron Cross, that King Wilhelm I

re-instituted the Iron Cross with an order dated 19 July

1870, the very day of his beloved mother Queen Luise's

death. He continues: On 30 July, the day before the

departure of the king to join his army, the president of the

General Order Commission, Adjutant General v. Bonin,

presented an 1870 Iron Cross, finished that same day, to the

king. Wilhelm himself wrote on the accompanying letter from

General v. Bonin: "Approved." Thus the order was

given to the director of the Iron Foundry, Bergrath Schmidt,

to begin casting the crosses according to the model. On 11

August, Director Schmidt announced to the jewelers

authorized to make the silver frames that the Iron Cross

cores could be picked up. Furthermore, Schneider recounts

his manufacturing figures in detail, and states in summary

that, by command of His Majesty the King, a total of 44,489

crosses had been delivered as of July, 1871 from the General

Order Commission to the Military Cabinet. The foundry to

which Schneider refers is the Royal Iron Foundry in Berlin,

founded in 1804 and located in front of the Oranienburger

Gate. In addition to the Royal Iron Foundry in Gleiwitz, the

Royal Iron Foundry in Berlin manufactured cores for Iron

Crosses during the Napoleonic Wars of Liberation. For our

purposes here, we must investigate the manufacturing

techniques and connections of the time. The Berlin Foundry

had a high technical "know-how," and when

undertaking to manufacture 1870 cores its artisans could

look back with pride on a long and successful company

history. From their workshops, for example, were built, in

1816, the first two gear-wheel steam locomotives in

continental Europe, the Kreuzberg Monument for the Wars of

Liberation in Berlin, and the Berlin castle bridge, which to

this day testifies to the Foundry's efficacy from its spot

on Berlin's Invalidenstraße. But the Foundry did not

undertake only large-scale projects. Its experience with

decorative artwork and delicate jewelry seemed to make it

the perfect choice to manufacture the cores for the Iron

Cross. Let us investigate the workshops and production

techniques to learn more about our subject. After the

confirmation of the new core design, the first step was to

make a wax model from which a master mold would be made with

a soft metal like tin or silver. Then sand -- sifted several

times through a linen cloth and kneaded with clay -- was

mixed with water and tapped by a hammer into the mold until

it was tightly compacted. After smoothing, the workpieces

were pressed in and then the second, already prepared side

of the mold could be attached and assembled under high

pressure. After the separation of the two halves -- which

could be accomplished without difficulty as the contact

faces had been powdered with coal dust before -- the master

pieces could be removed leaving the remaining imprints

connected by fine channels. This is how a so-called casting

tree was produced. After the finished casting molds dried,

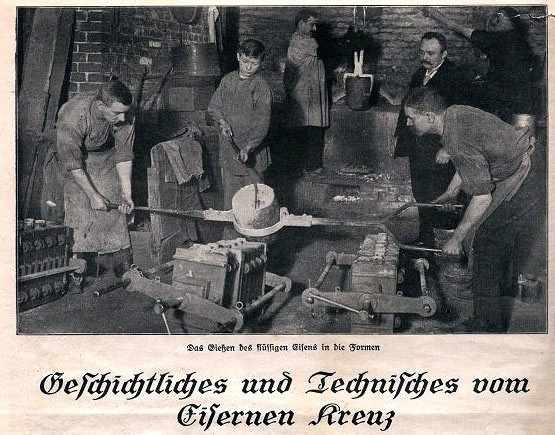

the actual casting began. Experienced workers poured the

molten iron from a melting pot into the provided openings of

the mold, where the iron flowed evenly into the hollows.

Through previously-applied outlets, the suppressed air

escaped. This technique allowed the production of high

quantities in the shortest time (Fig. 1).

Fig.

1: The illustrated magazine "Stein der Weisen,"

published at the beginning of World War I, shows the

tradional process for manufacturing the Iron Cross.

Initially, each core was cast. However, the astounsing

number of Iron Crosses awarded -- over 5 miliion in World

War I -- soon made other techniques necessary.

After the

solidification process of the iron, the molds were separated

and the cores removed by means of a slight knock, or tap, on

the side of the mold. With a polishing stone the cores were

finished by hand and given the desired look of fine jewelry.

Then followed the process of annealing, or removing inner

stress through a process of heating and gradually cooling

again. Next, the cores were again evenly heated, and a dark

varnish made from linseed oil, resin, and galena black

carbon was applied. A final rapid heating caused the oil to

evaporate, leaving the iron cores with that durable

matte-black finish typical of the Iron Cross. This finishing

process is also known as "false blackening," and

has nothing in common with real blackening in which there is

a chemical reaction of the base material itself and a kind

of patina forms. In the case of "false

blackening," a thin, highly adhesive coating adheres to

the core, creating the so-called "blackening."

From the evidence so far observed, we may now draw our first

conclusions. The majority of Iron Crosses awarded during the

campaigns of 1870-1871 must have identical cores, since they

were all manufactured at the Royal Iron Foundry in Berlin.

Minor differences are due to the aforementioned

manufacturing and finishing method. Only the frames should

exhibit marked differences, since they were made by several

different jewelers. But here again we must reference

Schneider, who states in his book that as late as March

1872, several thousand Noncombatant First and Second class

crosses remained to be awarded. He does not mention where

these later-awarded examples originated. A further order

from the Royal Iron Foundry is probable, and Schneider may

have made no mention of it on the assumption that it was

understood. With the following photo documentation we may

try to further understand our subject. It should be noted

that an assignation of a manufacturer to the 1870 EK2 can

only come from comparison with marked First class

crosses(Fig. 2).

Fig.

2: Iron Cross First Class marked for Johann Wagner &

Sohn, Berlin

Exactly

this core type, with its distinctive date and crown design

(Fig. 3), is to be found on most Second class Iron Crosses,

and it may be assumed that it is this type described by

Scheider and made in the Berlin Foundry.

Fig.

3: Iron Cross Second Class. The core design is identical to

the FIrst Class example illustrated above.

Further

clues are to be found in the available literature on the

history of military decorations. Jorg Nimmergut, in Volume 2

of his book, German Medals and Decorations to 1945, shows an

engraved EK1 from ex-Kaiser Wilhelm II's Huis Doorn, with a

core identical to those previously described. This cross is

his father Crown Prince Friedrich Wilhelm's personal

example, awarded on 20 August 1870. Also, former Chancellor

Bismarck's EK1, shown in the recently-published book of his

awards, exhibits an identical core. Furthermore, this core

type may be seen in contemporary photographs (Fig. 4-6).

Fig.

4: The War Minister to-be, Karl von Einem gen. von Rothmaler.

Fig.

5: Lieutenant General Bernhard of Austria

Fig.

6: Details of Iron Crosses worn by unknown recipients

This core

type shall now be designated "Type A." All

examined Iron Crosses with this Type A core have the

following characteristics: - The cores are cast. - The size

varies by tenths of a millimeter, and only very rarely

exceeds 42mm. - The weight can be between 15.6 and 17.5

grams. - The jump ring is affixed very near the top and is

usually open (unsoldered) on one side. Never has a maker

mark or a silver-content mark been seen on the ribbon ring.

(Fig. 7)

Fig.

7: Jump rings open (unsoldered) on one side.

The cores

are not painted, but blackened as described above (Fig.

8)

Fig.

8: Reverse of a "blackened" Type A core.

After

core Type A, we must now consider a second type with

different characteristics. Again, assignment of a maker has

been accomplished by comparison to marked First class

crosses. This core shall be called "Type B." The

illustrations show a First class Iron Cross made by Godet,

Berlin, and an example of a Second class with the same core

(Fig. 9-10).

Fig.

9: EK1 marked for Godet. Characteristics of this core

include the slim numbers in the date, the slightly leaning

"8", and the tall, narrow "0".

Fig.

10: EK2 with leaning "8" and high, slender

"0".

Supporting

contemporary evidence is again provided by "The Great

Nimmergut." There is a cross of this type in the

possession of Kaiser and King Wilhelm I and shown in The

Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation. This core type is

also easily discernable in contemporary photographs (Fig

11).

Fig.

11: The Type B core can clearly be seen on this unknown

veteran's bar. Photo: Aron Willers, Friedrichshafen.

Type B

cores have the following characteristics: - The cores are

cast. - The size varies by tenths of a millimeter, and

occasionally exceeds 42mm. - The determination of weights is

somewhat distorted by the fact that a number of examined

crosses exhibited repairs. At the lower end of the scale is

16 grams. However, it is important to note that no example

weighed over 17.6 grams. - The cores are not painted, but

blackened (Fig. 12).

Fig.

12: Reverse of a "blackened" Type B core.

- The

jump ring is also attached near the top, is usually open on

one side. Again, no manufacturers or silver-content marks

were seen. The evidence above permits the conclusion that

there were two contemporary core types, designated here as

Type A and Type B. The essential characteristics -- casting,

blackening instead of painting, high and almost identical

jump ring, weight and size tolerance -- are very similar.

Only in the design of the core details may differences be

found. The continuing pursuit of our quarry leads us to the

year 1874. Although not previously noted in the study of

this subject, it is nevertheless true that the Royal

Prussian Iron Foundry in Berlin was closed in this year.

Kaiser Wilhelm I issued the order for closing the Foundry on

31 March 1873, and the last cast was made on 5 January 1874.

The inventory of the foundry was sold at auction to other

state enterprises and institutions. Not only does this

development represent the end of a historically and

culturally valuable era of art and Iron work in Berlin, it

also raises the interesting question of who, after the

Foundry's closing, was able to manufacture cores to meet the

demand for replacement Iron Crosses. Inseparable from this

question is the existence of core Type B. As we have seen,

Type B cores were used by Godet of Berlin. Moreover, as of

this writing, they have been seen exclusively in Godet

crosses. There exist no other crosses clearly attributable

to a different manufacturer with this core type. This stands

in contrast to Type A cores, which are clearly to be found

in crosses assembled by jewelers other than Wagner of

Berlin. Let us remind ourselves of Schneider's observations:

"Director Schmidt announced to the jewelers authorized

to make the silver frames that the Iron Cross cores could be

picked up." If you infer from this statement that

several jewelers arrived to pick up the finished cores from

the Berlin Foundry, it becomes clear why Type A cores are to

be found enclosed within frames manufactured by multiple

companies, and why there are EK1s marked by various

jewelers, including Godet, with Type A cores (Fig. 13).

Fig.

13: EK1 with Type A core, but marked for Godet. Photo:

Markus Bodeux, Herne.

But Type

B cores are known only in Godet frames. We may now conclude

that Godet either made, or had made, Type B cores. An

interesting corollary may be found in secondary literature.

In Friedhelm Heyde's standard Iron Cross reference book on

the collection of Max Aurich, published in 1980, the author

writes about recipients of the 1813 Iron Cross who received

their awards after the end of the Napoleonic Wars: Whether

the casting of the iron cores was accomplished in the Kgl.

Preuß. Eisengießerei Berlin (Gleiwitz) or at the iron

foundry of the respected manufacturer of religious jewelry,

Godet, has not been conclusively established. This means, of

course, that Godet did have the means at their disposal to

make the iron cores themselves. Also, as anyone interested

in the history of military decorations is aware, there was a

strong urge for companies to keep everything in-house --

both manufacturing and design. Examples of Godet's own urge

to individuate their designs are to be found in their unique

swords, the completely different design of their First class

Prussian Red Cross medal, and their stylistically divergent

Prussian Stars. Core Type B, with its completely different

design, fits in this list rather nicely. Such a venture

would have been economically beneficial as well, for not

only were duplicate pieces needed, but replacement crosses

would have been required by those who either lost their

originals, or whose originals suffered from the common

breakage of the jump ring. The latter problem was already

known from the first crosses. Why the problem was not fixed

for later crosses is not known. Perhaps, as has been

suggested, the research and retooling required was not

cost-effective, an example of questionable craftsman logic.

(Fig. 14-15).

Fig.

14: Clearly visible is the repair to this EK2.

Fig.

15: A period repair to the jump ring.

At this

point we may make a preliminary summary of our findings:

Core Type A and Type B are both contemporary to the award

period. Type A cores, made at the Berlin Foundry, were

distributed to several jewelers, but predominantly Wagner of

Berlin, for use in award and private-purchase Iron Crosses.

Type B cores, probably manufactured in-house by Godet, were

used in duplicates and replacement crosses. In this context,

it is worth mentioning that crosses with core Type B are

found far more frequently mounted on medalbars (großen

Ordensspangen) than are Type A crosses, a fact which tends

to support the theory that they were manufactured as

secondary pieces. After this excursion into manufacturing,

production techniques and historical context, we must now

describe yet another type of cross. It is a type which can

not be found in any known period groupings, nor can it's

provenance be established by any other supporting

documentation or evidence. Moreover, it is only in recent

years that this type has been seen in the marketplace. This

statement is further confirmed by the fact that no examples

of this type may be seen in Friedhelm Heyde's book on the

Aurich collection. Neither can such a type be identified in

Harald Geißler's 1995 Iron Cross book. In Jorg Nimmergut's

previously cited book, published in 1997, there are only

images of core Type A and core Type B crosses. Only newer

publications, such as American author Steven Thomas

Previtera's The Iron Time, published in 2007, show this type

of cross. (Fig. 16-21)

Fig.

16: The two crosses in the top row are clearly larger than

the Type A and Type B core crosses in the bottom row.

The

characteristics of this type of cross are listed below: -

The cores are not cast, but stamped. - The crosses are

larger and vary in size from 42 to 44 millimeters. - They

are much heavier and generally weigh over 19 grams. - The

ninth bead in the headband of the obverse crown is generally

somewhat larger than the others, slightly offset to the

bottom, and quite noticeably protuberant.

Fig.

17: Obverse crown with protuberant ninth bead. Also note

maker's mark "Z" or "N" on the ribbon

ring.

- The

crossing lines on the "8" on the core date are not

on the same level as in Type A cores, but rather one crosses

noticeably over the other. This is known as an

"over-and-under 8."

Fig.

18: The "over-and-under 8.".

- On the

reverse side date, there are deep flaws in the lower

portions of the "8" and the middle "1".

Fig.

19: The date flaws on the reverse.

- The

jump ring is heavily soldered and sits lower on the frame;

the ribbon ring almost always exhibits a marker's mark.

Fig.

20: Maker's mark "L" on the ribbon ring, and the

characteristic ninth bead in the crown's headband.

- The

cores are all painted and not blackened.

Fig.

21: Clearly visible is the core's paint, and the oversize

ninth bead.

That

these crosses are not originals should be evident by

Schneider's remarks as well as by the total absence of

illustrations and discussions in earlier literature.

However, the argument that these are original pieces, or

contemporary duplicates, is heard time and again. There is

no doubt that there was a demand for replacement crosses.

Indeed, the need to address breakage problems and the 25th

anniversary of the Iron Cross's re-institution would have

raised this demand. Thus it is not proper to dismiss

outright any cross that does not have either a Type A or a

Type B core, as the market for second pieces surely gave

rise to different variants. Figures 22 and 23 show an

example that was certainly a contemporary secondary piece.

The painted core of this example resembles a Type A, but

clearly deviates in some details.

Fig.

22: Obverse of a replacement cross.

Fig.

23: Reverse of a replacement cross.

However,

in light of known manufacturing techniques, the cross is

question shows itself to be highly suspicious. Size and

weight of these pieces correspond to the average values of

World War I Iron Crosses and are significantly over accepted

tolerances for core Type A and core Type B 1870 Iron

Crosses. The jump ring attachment is identical to 1914 EK2s,

and the stamped cores are painted, again as with 1914 EKs.

But the list of suspicions is not yet exhausted. Maker's

marks are found on the ribbon rings. These markings are

easily identifiable as World War I codings. At this point,

the weight of the evidence clearly establishes that these

crosses are modern counterfeits, or fakes, made from newly

minted cores and genuine World War I Iron Cross frames. This

fake is called "The Ninth Bead Fake," and is known

with the following maker's marks on the ring: L, WS, Wilm, N

or Z, KO, CD 800, MFH, G, K.A.G., L.W., IVI, R-W -- next to

KO, K.A.G. and CD, the most common maker's marks from

1914-series Iron Crosses. The instinctive notion that these

may be legitimate duplicates made for veterans during World

War I may be rejected on two counts: first, the logic of

biology dictates that demand would have been very low for

1870 Iron Crosses after 1914, and second, no contemporary

manufacturer could have made the quantity of these Ninth

Bead Fakes on the market today and still met their

obligations to manufacture 1914-series crosses; they

dominate today's market in disconcerting numbers. It would

be a mistake, however, to imagine that there was no

production of 1870 Iron Crosses after 1918. There was indeed

a small, but verifiable, production of such awards. The

manufacturing quality of Ninth Bead Fakes, however, does not

compare favorably with World War I-made pieces. This

discrepancy, combined with their increased numbers in recent

years, does not permit any classification other than

contemporary fake. This verdict is further supported by the

extremely unprofessional way the frame halves have been

rejoined after the cores were exchanged. Original pieces

always exhibit a finely soldered seam -- testimony to the

high skill of contemporary silversmiths. Mastery of this

skill may be confidently assigned to World War I-era

craftsmen also; thus the Ninth Bead Fakes can not have been

made during either period. Moreover there is not even the

slightest possibility that the frames were opened and

rejoined during World War I, as anyone with a need would

have had access to freshly made original frames (Fig. 24).

Fig.

24: A selection of poorly resoldered frames on examples of

the "Ninth Bead Fake."

This last

unambiguous evidence that the Ninth Bead examples are fakes

-- the unprofessional resoldering of the frames -- may

signal the final disappearance of these fakes from the hobby

and the market. But the final farewell may not have yet been

heard, unfortunately, for it must be mentioned that,

although rare, First Class examples of this fake have been

seen.

Special

Thanks to: Trevor, Markus Bodeux, Herne, Michael Fischer, Ladenburg

and an anonymous specialist.

Literatur:

Arndt, L. / Müller-Wusterwitz. N., Die Orden und

Ehrenzeichen des Reichskanzlers Fürst Otto von Bismarck,

Offenbach, 2008. Geißler, H., Das Eiserne Kreuz,

Norderstedt, 1995. Hessenthal, W. v. / Schreiber, G., Die

tragbaren Ehrenzeichen des Deutschen Reiches, Berlin 1940.

Heyde, Friedhelm, Monographien zur Numismatik und

Ordenskunde, Preußen-Sammlung Max Aurich, Teil C, Das

Eiserne Kreuz, Osnabrück, 1980. Meyers großes

Konversationslexikon, sechste Auflage, Leipzig und Wien,

Bibliographisches Institut, 1905. Nimmergut, J., Deutsche

Orden und Ehrenzeichen, Band 2, München, 1997. Previtera,

S.T., The Iron Time, Richmond, 2007. Schneider, L., Das Buch

vom Eisernen Kreuze, Berlin 1872 Schreiter, Ch. / Pyritz,

A., Berliner Eisen, Hannover, 2007

©

Andreas M. Schulze Ising VII/2009

|